a sermon on 2 Corinthians 5:16-21 and Luke 15:1-3, 11b-32

preached on March 6, 2016, at the First Presbyterian Church of Whitestone

One of the most amazing things about the Bible is the way the same stories manage to slip into our lives over and over again. Somehow this great collection of writings manages to carry some sort of meaning in every generation. When things in the world are changing, these ancient stories still speak to our present realities. When the situations in our lives shift for one reason or another, these same stories take on new meaning for us. And when we need comfort amid turmoil in our lives, these stories give us hope for God’s presence through it all.

We need look no further than our reading from Luke this morning for a perfect example of all these things. The parable of the prodigal son told by Jesus in Luke 15 manages to use the same words to speak volumes of meaning into radically different times and places. Every time I turn to this text, I am reminded of something different about who God is. Each time I hear these words, I get a glimpse of the many different ways God loves us. And each time I hear this story, I find myself entering into the parable from a different perspective—some days it is as the younger son, some days as the older, some days as some other minor character around the edges of it all, some days even the father.

Wherever we enter this incredible story, though, from whichever viewpoint seems clearest to us in this particular moment, we gain a glimpse of the grace of God streaming into our world in all time. Grace permeates every moment of this parable. Even the setting for its telling is a moment for grace—Jesus had stirred up trouble with the Pharisees and scribes because of the company he kept, because he welcomed tax collectors and sinners and ate with them, so he wanted to help them understand why he responded to their gracelessness with compassion.

The story, like the setting of its telling, is filled with moments of gracelessness. It opens with the younger son showing no grace whatsoever as he asks to receive his inheritance while his father is still alive. It is as if the son told his father that he was as good as dead to him, that he was worth nothing more to him than the value of the things that he owned. The father had the opportunity to respond with the same lack of grace that was shown him, but he chose to give his son what he asked for.

As the son wandered the surrounding lands and squandered his inheritance, he experienced a similar lack of grace like what he offered to his father from those he encountered. The people of his new homeland saw no reason to show this stranger in their midst any sort of grace. They treated him solely as a hired hand, leaving him to fend for himself in the midst of a severe famine, not even suggesting that he ought to take some of the food that he was feeding to the pigs to sustain himself. The son showed so little grace to himself along the way, too. He counted himself so worthless that he would not even be treated as a son by his father, that his father’s grace toward him had long run out, that he was so deeply undeserving of any care other than as a hired hand.

Amid all the gracelessness of this story, the younger son’s return home was filled with great grace. His father’s grace upon his return was so abundant and so much at the ready that he seemed to be on the lookout for his son’s return each and every day, and so he ran to greet him when he saw him from far away. This greeting was not one of stern rebuke but rather warm welcome. Before the son could even finish his carefully rehearsed speech begging for mercy, his father called for a robe, ring, and sandals, then he made plans for a great feast and celebration to welcome the lost son home.

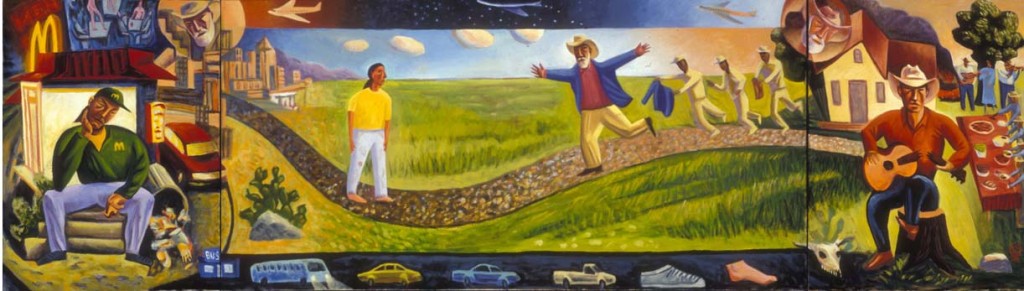

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Return of the Prodigal Son

Amid all the grace shown in this story, the older brother was not particularly excited about his father’s generous welcome to his deadbeat younger brother—it seems that the deep grace of the father had not been passed down to either one of his sons! But the father would not let his older son’s gracelessness undo the grace that defined his life and he was so willing to share. When the older son protested that he had remained at home, working faithfully and diligently while his brother had “devoured [the] property with prostitutes,” and had enjoyed none of these gifts that had suddenly been showered upon him, the father reminded him that the kind of grace shared with his brother was also shared with him, too, but that this moment was worthy of celebration, for “this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.” No matter how much the older son might try to derail it, no matter how badly the circumstances were set with gracelessness, even no matter how difficult it might be for the younger son to accept it, the father insisted in his words and actions that grace would shine through.

In the end, Jesus’ parable is about grace—grace that gives more than we think we can receive, grace that opens us to a radically different way of relating to God and one another, grace that fills even the most graceless places of our world with God’s mercy, compassion, peace, and life—and this parable helps us to see how that grace can take hold in our lives and our world. When it does, we can do what Paul suggests in our first reading, from now on to “regard no one from a human point of view,” to embrace the new creation that comes to us in Christ, to make our lives marks of reconciliation and grace each and every day.

I suspect none of this made much sense to Jesus’ disciples as he told this parable as he made his way to Jerusalem. They probably grumbled about the kind of people who showed up when Jesus welcomed tax collectors and sinners. The disciples may even have found themselves more in line with the devoted older son, complaining about all the people who managed to join the crowd along the way when they had been with Jesus from the beginning. And while they may have appreciated his pointed criticism of the Pharisees and the scribes, we know that in the end they weren’t quite ready to put their own lives on the line to join him in this message. But as time went on, as the light of the resurrection shone upon them, it all finally began to make sense, for the resurrection of Jesus showed them that his death brought a new meaning of grace to everyone. The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus ultimately made it clear that his parables about God’s generosity and grace were not just pipe dreams. No—the grace that the father embodied in this parable was the very same grace that was possible and real for everyone because of the reconciliation made possible in Christ.

As hard as it was for the disciples, living such grace is not easy for us, either. It is so much easier to choose to exclude those people who look or act or live differently than we do, to join the Pharisees and scribes in their grumbling about who gets welcomed in and who gets fed, to be so tightly bound by our rules that we end up like the older son and miss the joy that comes when transformation takes root and hold in our world. As hard as it is to show this grace to others, it can just as difficult to show this grace to ourselves. It is all too easy to end up like these brothers, so stuck in assumptions that we do not merit the generosity of God’s grace because of the depth of our wrongdoing or so mired in the despair of legalism as we focus on our own understanding of doing what is right that we miss the opportunity to share the joyous celebration offered when others come to know God’s grace in new ways. Our humanity makes it all too easy to exclude others and even ourselves from the abundance of this grace, but Jesus’ parable and Paul’s words remind us that this is no longer the way we are to live. We are called to set aside the gracelessness that comes to us so naturally and embrace the abundant grace of God in our lives as we become a part of God’s new creation.

So as we journey through these Lenten days, as we walk with Jesus on the way to the cross, may God show us how to welcome this grace more deeply in our own lives, may God help us to set aside our fears of those who might join us in benefiting from this incredible gift, and may God fill us with grace anew as we see others from this new point of view of mercy, peace, hope, and grace, as together we wait, watch, and work for the new creation to be revealed in our midst by the power of Jesus Christ our Lord.

Lord, come quickly! Amen.